Carl Jung’s theory of analytical psychology strives to explain behavior patterns by analyzing the human psyche. Jung’s theory is a multifaceted psychological framework that delves as much into psychiatric pathology as it does into mysticism. However, the theory revolves around a sophisticated psyche model in which conscious and unconscious elements integrate to shape the individual’s experiences and behavior.

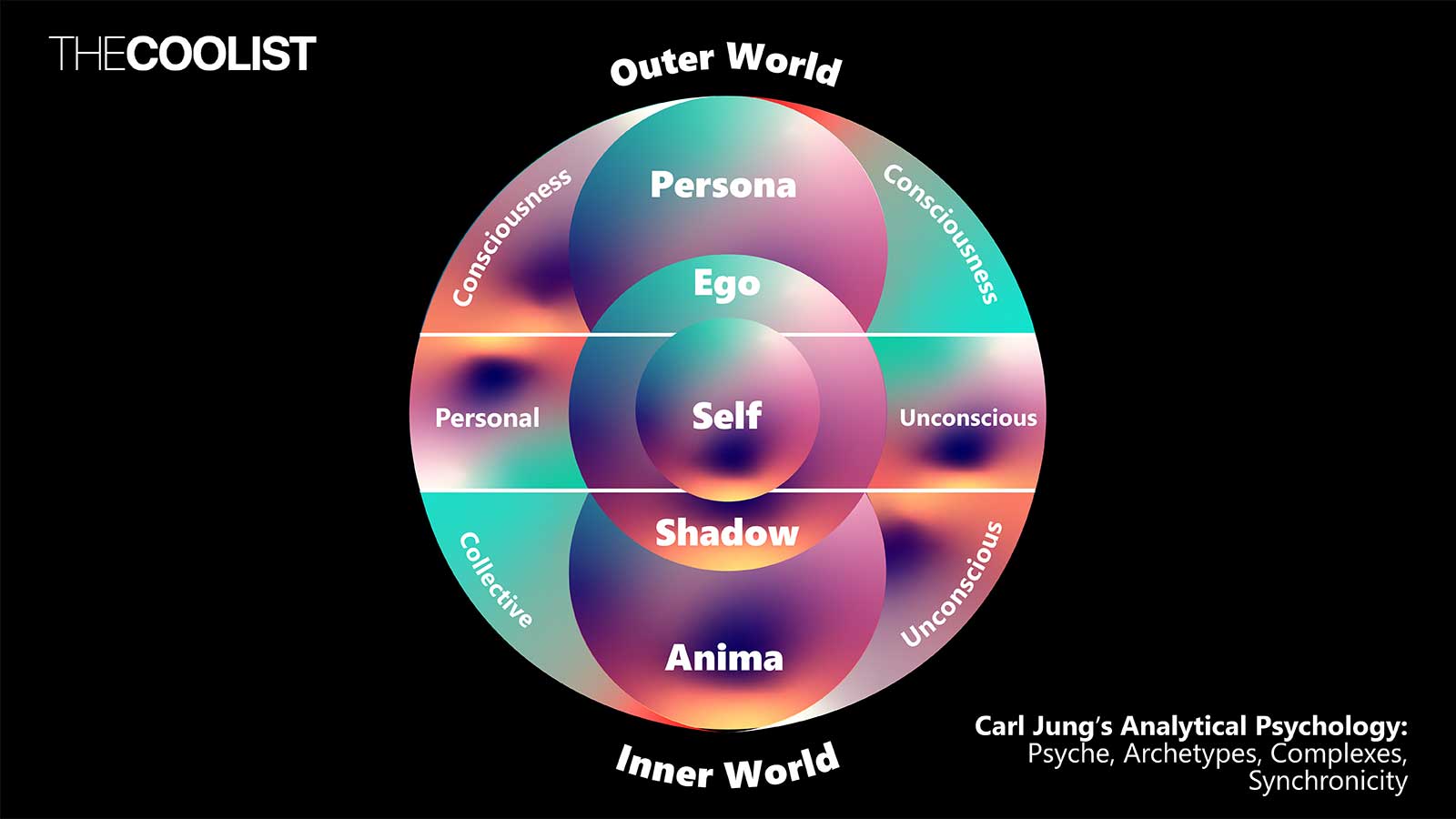

Jung’s psyche model is a complex network comprising the ego, the personal unconscious, and the collective unconscious. The ego is the manifestation of our conscious identity, according to Jung. Meanwhile, the personal unconscious is the hidden part of the psyche that evolves throughout an individual’s life. This part of the unconscious houses the complexes—patterns we develop based on life experiences, which then shape our behavior. Finally, the collective unconscious comprises the deepest level of the psyche that’s universal and shared by all of humanity. This part of the psyche contains archetypes: psychological patterns humanity has inherited throughout its existence. The concept of the collective unconscious and the archetypes that reside in it is Jung’s most notable (and controversial) contribution to psychology, as the concept is steeped in mysticism and echoes many of the world’s mythological and religious traditions.

Below is a thorough analysis of Carl Jung’s analytical psychology theory, psyche model, personality type framework, and synchronicity, as well as an overview of the influences that inspired and shaped his work.

Jungian psyche composition

Carl Jung’s psyche model is a representation of our inner world that forms the core of his analytical psychology theory. A key aspect of Jung’s psyche model is the central role of the unconscious. Unlike earlier psychological models, Jung believed the unconscious has an outsized influence on our thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and sense of self.

The three essential components of the Jungian psyche model are the ego, the personal unconscious, and the collective unconscious, as explained below.

The ego

The ego in Jungian psychology represents the part of the psyche responsible for our sense of self and identity. The ego is what allows us to say “I” and experience ourselves as distinct entities within the world.

Jung believed that a well-developed ego is crucial for a wholesome and balanced personality. The ego’s development begins in childhood and continues throughout our lives. As we navigate individuation, the ego is responsible for logical thinking, decision-making, and maintaining a sense of continuity in our identity. However, Jung believed that investing heavily in the ego fragments our sense of self because it limits the potential for wholeness within the unconscious.

In Jungian theory, the ego communicates continuously with the personal unconscious. Memories, experiences, or emotions that the ego struggles to confront usually become repressed into the personal unconscious. Conversely, dreams, symbols, and spontaneous insights are the personal unconscious signals to the ego.

The personal unconscious

The personal unconscious is a concealed part of the psyche unique to each individual. It houses our memories, emotions, impulses, as well as experiences we’ve pushed out of conscious awareness. The personal unconscious may harbor repressed emotions, forgotten childhood events, or elements of our lives that haven’t received conscious focus. According to Jung, a key feature of the personal unconscious is the presence of complexes—patterns that affect our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

Complexes

Jungian complexes are emotionally charged clusters of thoughts, feelings, and memories that reside in the personal unconscious. Complexes shape our behavior, motivations, and relationships, often without conscious awareness. We develop complexes through difficult experiences, unresolved conflicts, or archetypal forces that operate beneath the surface of the conscious mind.

Below are five of the most prominent Jungian complexes.

- Mother complex: Involves unresolved issues with the mother figure, and may lead to dependency, difficulty with boundaries, or an over-idealization of the feminine.

- Father complex: Focuses on unresolved issues with the father figure, and often causes struggles with authority, approval seeking, or difficulties forming a sense of self-worth.

- Inferiority complex: A sense of inadequacy and self-doubt that may lead to overcompensation or social withdrawal.

- Power complex: A preoccupation with control and dominance that most likely stems from an underlying fear of vulnerability.

- Persona complex: Overidentification with one’s social mask, which may cause the individual to neglect their inner world and consequently feel inauthentic.

Complexes often harbor difficult or repressed material, but Jung believed that they also conceal creativity and suppressed strengths. Consciously exploring our complexes helps us understand our behavioral patterns and tap into these highly beneficial (yet hidden) elements of our personality. Methods like dream analysis and active imagination are effective tools for accessing and integrating these hidden aspects of ourselves. Understanding the personal unconscious and the complexes it hides is a key step in individuation and a gateway to the deepest, universal psyche layer: the collective unconscious.

The collective unconscious

The collective unconscious is a reservoir of psychic energy and patterns shared by all humanity. It’s the deepest psyche layer according to Jung, who stated, “The collective unconscious is the sediment of all the experience of the universe throughout all time […]” While individual experiences shape the personal unconscious, the collective unconscious is the imprint of our evolutionary past. It houses primordial patterns, known as archetypes, which form the basis of shared human experiences.

The concept of a shared psychic inheritance has roots in various philosophical and spiritual traditions. For example, Plato’s ideal “Forms,” and Romantic philosophers’ emphasis on intuition hint at an unconscious dimension beyond the individual. Likewise, Eastern philosophical concepts, such as Atman and Brahman in Hinduism, the Buddhist notion of emptiness (Sunyata), or the Tao in Taoism, all point to a connection between the individual mind and a deeper, universal awareness.

Meanwhile, Jung placed his collective unconsciousness concept within his broader psychological framework, in which the primordial archetypes interact with other parts of the psyche and shape our behavior. These archetypes find expression in our dreams, myths, religions, and art, shaping how we perceive the world and respond to fundamental life experiences.

Jung devised the collective unconscious theory by comparing his clinical observations to universal patterns and images that exist across cultures. He noticed recurring patterns in his patients’ dreams and fantasies that seemed to transcend their personal experiences and mirror those found in ancient mythologies. Jung’s cross-cultural studies reinforced his belief in a shared psychic inheritance, which manifests as archetypes. This led Jung to theorize that the collective unconscious holds ancestral memories etched into the very structure of the psyche.

Jungian archetypes

Jung’s archetypes are psychological patterns inherited over millennia of human evolution and concealed deep within our collective unconscious. These primordial blueprints shape our perceptions and behaviors. Archetypes are not static; they are dynamic tendencies that each individual expresses in unique ways that stem from their personality and cultural context.

As Jung observed, “The archetypes are the imperishable elements of the unconscious, but they change their shape continually.”

Jung came up with his concept of archetypes based on extensive research and observations as a clinical psychiatrist. He noticed recurring patterns and potent symbols in his patients’ dreams, artwork, and fantasies. Moreover, his studies of mythology, religion, and folklore in different cultures showed striking parallels in themes and imagery. These similarities in cultures with no historical contact suggested to Jung an underlying structure within the human psyche (which he termed the collective unconscious), where these innate universal archetypes reside.

Jung’s research revealed an enormous number of archetypes. The five most prominent of these are as follows:

- The Persona

- The Shadow

- The Anima and Animus

- The Self

- The Hero

Persona

Jung’s Persona archetype (derived from the Latin word for “mask”) is the carefully constructed facade we present to the world. This facade comprises the behaviors we adopt and the image we project to navigate different social situations and fulfill societal expectations. For example, a person might have a professional persona at work, a different one within their family, and yet another with their circle of friends.

This concept of a presented self exists in various cultures. Throughout history, it has manifested in the theatrical masks of ancient Greece, the idea of “face” in East Asian cultures, and in societal expectations in the West. However, Jung proposed that the tendency to create a “persona” was rooted in a universal archetype, so it was present within all of humanity. In his theory, Jung connected the Persona archetype to a broader psychological framework with specific functions and dangers.

Jung thought that the Persona was a necessary social function. However, he emphasized that the Persona does not capture the entirety of who we are. Rather, it represents a curated selection of our personality, designed to elicit specific responses or achieve desired outcomes. Jung warned that the danger lies in over-identifying with our persona. When we become invested in our outward image, we lose touch with our genuine selves. This imbalance leads to inauthentic relationships, a sense of emptiness, and difficulty navigating situations where our persona doesn’t fit.

Jung theorized that the persona’s development stemmed from our innate need to belong, to which end we project an acceptable version of ourselves. Consequently, Jung believed the Persona is closely linked to the Shadow archetype, which holds all the aspects of ourselves we deem unacceptable and try to hide. Often, what we present as our ideal persona is the direct opposite of the traits we repress in our shadow.

Shadow

Jung’s Shadow archetype represents the hidden (and often unconscious) aspect of our personality. It contains elements we deem unacceptable about ourselves, such as negative traits, repressed desires, uncomfortable emotions, and unacknowledged impulses. We push these elements out of conscious awareness due to personal shame, societal disapproval, or traumatic experiences. However, Jung argued that the Shadow may also hold suppressed positive elements, such as creativity.

The idea of a darker, hidden self has existed throughout history. Mythologies and religions often feature figures like the trickster, the Devil, or other shadow-like characters embodying chaos, desire, and generally socially unacceptable aspects of humanity. Literature additionally explores the Shadow archetype with works like The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, where the main character battles a monstrous alter ego. Meanwhile, Jung framed the Shadow within a specific psychological model. He saw it as a universal archetype concealed in the collective unconscious.

“Everyone carries a shadow,” Jung asserted, “and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is.”

Jung believed that the most significant risk of an unacknowledged shadow is projection. In this process, a person unconsciously sees their own disowned traits in others, which leads to judgment and conflict. Often, qualities we reject in ourselves and relegate to the Shadow then project onto figures of the opposite sex, thus forming the Anima and Animus archetypes in Jungian theory.

Effectively managing the influence of the suppressed elements in one’s shadow requires a conscious effort to integrate the Shadow instead of fighting it, according to Jung. Doing so is a challenge, but the process promotes greater self-awareness and wholeness.

Anima and Animus

Jung’s Anima and Animus archetypes represent innate elements of the opposite sex that each person unconsciously harbors in their psyche. The Anima is the unconscious femininity within a man’s psyche, while the Animus represents the unconscious masculine qualities in a woman. These archetypes influence how we relate to people of the opposite sex, and often manifest through projection—the unconscious tendency to see our inner qualities in others. This tendency can lead us to idealize or demonize partners. Jung believed that the Anima and Animus archetypes stemmed from biological factors, ancestral experiences with the opposite sex, and the vast imagery of the collective unconscious.

The principle of a contrasexual inner part of the psyche existed long before Jung. Many ancient mystical traditions recognized the dynamic interplay between feminine and masculine energies within each individual. For example, the Taoist philosophy of yin and yang states that the universe is composed of two complementary and interconnected forces. The feminine yin is receptive, dark, and yielding. Meanwhile, the masculine yang is active, light, and penetrating. Similarly, Hermetic alchemical writings highlighted the importance of masculine and feminine principles uniting in a person’s spiritual and psychological transformation.

Jung likewise believed in the importance of integrating the Anima or Animus figures within one’s psyche. Instead of suppressing or fighting against the contrasexual parts of our psyche, acknowledging them and understanding their influence helps us develop self-awareness and a more balanced self. Moreover, our inner hero often relates to and interacts with our anima or animus, which also helps us shape the path to a more wholesome personality.

Hero

Jung’s Hero archetype personifies universal human transformation. It represents our innate drive to overcome challenges, transcend limitations, and pursue self-discovery.

The Hero archetype echoes through history. From ancient myths and legends to modern stories, famous heroes point to humanity’s fascination with tales of courage, sacrifice, and triumph over evil. Figures like Hercules, King Arthur, Artemis, and Joan of Arc are prime examples of this pattern. In most accounts, the Hero’s journey begins with a call to adventure that initiates the character’s quest into the unknown, with the Hero ultimately facing trials, setbacks, and foes. These encounters test the Hero’s strength, courage, and resolve, and mirror our struggles. Additionally, many narratives involve a symbolic descent into darkness, often to confront the Shadow, which precedes a rebirth or transformation.

According to Jung, the Hero archetype embodies the ego’s struggle to free itself from the unconscious and forge its own identity. Through the challenges and victories of the Hero’s journey, the ego develops strength, resilience, and a clearer sense of self. Ultimately, the archetype interacts with Jung’s Self archetype by driving the person toward wholeness.

Self

Carl Jung believed the Self was the central archetype in the psyche because it represents wholeness, unity, and the organizing principle of our personality.

The idea of a true self or unifying core is present in various philosophical and spiritual traditions. For example, in Hinduism, the concept of Atman represents the unchanging essence of the individual, while in Gnosticism, the true, divine self is obscured and requires effort to uncover and understand.

Meanwhile, Jung asserted that the Self comprised the conscious and unconscious elements, as well as the potential for both “good” and “evil.” Jung’s concept of the Self emerged from his study of these cultural traditions, as well as his clinical observations and own introspection. His extensive cross-cultural studies of mythology and religion revealed universal symbols and narratives of integration. At the same time, Jung’s observations as a clinical psychiatrist revealed recurrent patterns of wholeness and unity within his patients’ psychological struggles. Finally, Jung’s bouts of intense introspection (notably those he documented in the Red Book) also shaped his understanding of the Self archetype.

In Jungian theory, the Self is not synonymous with perfection. Rather, this archetype represents the totality of who we are. An individual’s recognition and integration of the different aspects of the Self comprised the journey toward wholeness—a process Jung called individuation.

Individuation

Individuation in Jung’s theory is a lifelong journey of psychological development that involves the integration of the conscious and subconscious elements of the psyche. It’s not a static destination, but rather the process of becoming a more whole and authentic individual.

Firm control over elements in the unconscious part of the psyche is the driving force behind individuation. This includes acknowledging our shadow, exploring dreams, understanding the unconscious mind’s symbolic language, and recognizing the archetypes that shape our inner lives. As Jung asserted, “Individuation means becoming an individual, and, in so far as ‘individuality’ embraces our innermost, last, and incomparable uniqueness, it also implies becoming one’s own self.” Notably, individuation isn’t a quest for a flawless ideal. Rather, it’s the embrace of our wholesome Self.

Jung’s individuation theory emerged from two key influences: his own introspection and clinical observations. Jung’s mid-life crisis pushed him to explore his own unconscious. This experience gave Jung insight into the discovery and integration of the psyche’s hidden aspects. Likewise, Jung noted that patients who actively engaged with their unconscious (for example, through dream analysis) often experienced greater personal growth.

Individuation is closely tied to Jung’s concept of actualization, which represents the realization of our potential. Individuation is the primary mechanism in this process.

Actualization

Jung’s actualization concept represents the realization of our full potential, where we become the most authentic and complete version of ourselves as we progress through individuation. Jungian actualization is similar to Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, as it recognizes a drive toward self-fulfillment. However, Jung’s perspective is more focused on internal integration instead of external needs and emphasizes the unique path each individual must forge. Crucially, Jung theorized that actualization involved recognizing and integrating aspects of one’s personality to achieve greater wholeness.

Jungian personality types

Jungian personality types are the framework Carl Jung devised for grasping the differences in how we perceive the world, process information, and make decisions. He believed that we are born with preferences that influence our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. These preferences are not rigid categories, but rather fluid tendencies within a broader personality spectrum.

Notably, Jung emphasized that no single personality type is superior. Each type holds strengths and potential blind spots. The goal of psychological development, according to Jung, is to become more aware of both our dominant and less-developed sides. By integrating these different (and often opposing) aspects of ourselves, we move towards greater wholeness and balance.

Jung’s typology comprises the following three main components:

- Attitude-types

- Function-types

- Psychological Types

Attitude-types

Introversion and extraversion are the two attitude types in Jungian typology. These attitudes describe the fundamental ways in which we direct their energy and attention.

Introverts mostly focus their energy inward. They explore their inner world of thoughts, feelings, and ideas, and overly stimulating environments feel draining for them. That said, introversion does not equate to shyness or social anxiety. Introverts often enjoy social interaction, but simply find their greatest sense of well-being through inner exploration. Additionally, they need periods of solitude and reflection to recharge after socializing.

Conversely, extraverts primarily focus their energy outward. They thrive on social interaction and engage with people, places, and activities in the external world. Extraverts enjoy being active and often gain energy from contact with others. However, extraversion does not mean superficiality. Extraverts can find deep meaning in relationships and experiences within their active, outwardly oriented lives.

Most individuals fall somewhere along a spectrum between introversion and extraversion, and pure introverts or extraverts are rare.

Function-types

Jung’s function types are a system for classifying the ways we perceive information and make decisions. When Carl Jung’s clinical observations revealed that introversion and extraversion alone couldn’t fully explain behavioral differences, he proposed the existence of four functions: Thinking, Feeling, Sensation, and Intuition.

Jung categorized Thinking and Feeling as “rational” functions since they mostly focus on making decisions. Meanwhile, he termed Sensation and Intuition “irrational,” as they are more concerned with how we take in information.

Individuals with a dominant Thinking function are logical and objective and prioritize cause-and-effect analysis. They focus on impersonal principles, rules, and consistency when making judgments. Their strengths lie in problem-solving, clarity of thought, and the ability to make fair decisions. However, a common weakness of people with a dominant Thinking function is that they undervalue emotions and the subjective human element when making decisions.

Those with a dominant Feeling function prioritize personal values, harmony, and the impact of decisions on others over hard logic. They strive to understand the subjective experience and make decisions based on compassion. Feelers’ strengths lie in understanding interpersonal dynamics and approaching situations with deep empathy. However, Feelers’ major blind spot is that personal bias and emotions often exert significant influence over them and hinder objective judgment.

Individuals with a dominant Sensation function are attuned to the physical world. They focus on concrete facts, practical details, and information they gather through the five senses. Their realism, groundedness, and ability to notice details others miss are their greatest strengths. These strong points help Sensation personalities excel at practical tasks and learn through hands-on experience. However, those with a Sensation function tend to overlook the bigger picture, miss symbolic meanings, and struggle to understand abstract ideas.

People with a dominant Intuition function focus on patterns, possibilities, and the flow of information across time. They operate through hunches and make connections that might seem intangible to others. Innovation, creativity, and recognizing long-term potential in situations or people are the main strengths of Intuition-dominant personality types. However, Intuition personality types generally loathe dealing with minutia, and this distaste for practical details often gets them carried away by ungrounded ideas.

Jung theorized that each individual has one dominant function and an opposite, inferior function that operates in the unconscious. Psychological development and individuation in Jungian theory entail consciously developing these non-dominant functions, as the process promotes greater wholeness of the personality. However, Jung ultimately believed that a well-rounded personality requires a balance of all four functions.

Psychological types

Jung’s psychological types represent the combination of a dominant function (Thinking, Feeling, Sensation, or Intuition) with an attitude (Introversion or Extraversion). This merger results in eight primary types below.

- Introverted Thinking: Focuses on logic, consistency, and objectivity, and analyzes cause-and-effect relationships. Introverted Thinking individuals with this type are reserved and precise in their thoughts and language.

- Introverted Feeling: Prioritizes personal values and internal harmony, and makes decisions based on what feels right. Introverted Feeling types with this type focus inward and are strongly attuned to their own emotions.

- Introverted Sensing: Focuses on concrete details and past experiences, learns through direct observation, and is aligned with the present moment. Those with an Introverted Sensing type have a calm demeanor, remember details well, and value practicality.

- Introverted Intuition: Focuses on patterns and possibilities, trusts insights and hunches, and sees connections others miss. Individuals with the Introverted Intuition type face inward and are drawn to the symbolic and theoretical.

- Extraverted Thinking: Focuses on logic, efficiency, and organizing the outer world. Extraverted Thinking individuals are problem-solvers who strive to impose order on their environment.

- Extraverted Feeling: Prioritizes interpersonal harmony, understands others’ emotions, fosters connections, and makes decisions based on a set of values. Individuals with the Extraverted Feeling type are outgoing, empathetic, and excel at creating a sense of belonging.

- Extraverted Sensing: Focuses on experiences in the immediate environment and enjoys action. Extraverted Sensing individuals are sociable, practical, and have a keen eye for aesthetics.

- Extraverted Intuition: Focuses on possibilities in the external world, enjoys change, and explores new ideas. Extraverted Intuition type individuals are resourceful, enthusiastic, and have a knack for seeing opportunities others might miss.

The psychological types above are based on the dominant function. However, Jung believed that each person possesses an inferior function that’s opposite to their dominant one. This less-developed function often operates unconsciously. Moreover, we access all functions to varying degrees. Our environment, life stage, and conscious choices influence the way we express these functions in our behavior.

Jung’s concept of psychological types offers comprehensive insights into personality and behavior. However, understanding individuals solely through a typological framework has limitations – according to Jung himself. He claimed that synchronistic events, which are innately linked to the unconscious, point to a realm where archetypes and experience intersect to transcend the most intricate of personality theories.

Synchronicity

Synchronicity is a Jungian concept that refers to coincidences that are so meaningful they defy simple chance. His clinical studies showed that certain external events inexplicably mirrored an individual’s inner state. This phenomenon hinted at a strong bond between the psychic and physical realms. Consequently, Jung believed that synchronicity was the manifestation of an acausal connecting principle underlying reality—one that outstrips our understanding of cause and effect.

The theory of synchronicity emerged from Jung’s clinical research. He noticed that his patients often experienced meaningful coincidences, especially during life transitions or relating to powerful dreams and symbols. Jung himself observed such phenomena, famously noting, “Synchronicity is an ever-present reality for those who have eyes to see.” Jung’s collaboration with physicist Wolfgang Pauli led him to propose that synchronistic events might point to a non-causal order within the fabric of the universe.

Jung theorized that archetypes could act as a bridge between this mystical dimension and the observable world. When an external event aligns with a highly symbolic theme or emotion within our psyche, synchronicity amplifies the archetypal energy. These occurrences often leave us in awe and wonder.

One of Jung’s most famous synchronicity examples involved an overly rational patient who resisted exploring her unconscious. As she described to Jung a dream involving a golden scarab, a scarab-like insect appeared at the window. Jung believed this synchronicity helped break through her resistance and open her to the potential for inner transformation.

Jung devised the “synchronicity” phenomenon within the context of psychology, but the concept of meaningful coincidences and acausal connections has far older roots. Like Jung’s synchronicity, ancient Chinese divination systems like the I-Ching rest on the belief that random events reflect a deeper universal order. Likewise, Hermeticism, alchemy, and other mystical traditions point to a dimension of reality where individual human consciousness forms part of a larger, universal whole.

There is no empirical evidence to support the existence of synchronicity. But despite criticisms of its subjective nature and lack of scientific proof, synchronistic experiences open us to the possibility of universal forces beyond comprehension. As such, the concept continues to fascinate philosophers, psychologists, and mystics alike.

What was the relationship between Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud?

Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud had a complex and ultimately fractured professional relationship, which contributed to the development of psychoanalysis and depth psychology.

Initially, Freud saw Jung as his intellectual heir—the champion who would carry psychoanalytic ideas beyond the confines of Vienna. Freud was a Jewish scholar researching the controversial field of psychoanalysis in a Europe that was steeped in antisemitic sentiment. Meanwhile, Jung was a brilliant, non-Jewish psychiatrist who could lend legitimacy to Freud’s controversial psychoanalysis theories. Jung, in turn, was drawn to Freud’s pioneering work on dreams, neurotic symptoms, and the power of the unconscious. Their discussions and extensive correspondence laid the foundation for many core psychoanalytic concepts.

However, the two men had fundamental differences in their understanding of the unconscious and the libido. Over time, these differences created an unbridgeable rift. Jung’s emphasis on spirituality, his concept of the collective unconscious, and his interest in mythology diverged from Freud’s focus on sexuality and personal repression. Personal tensions worsened their scholarly disagreements, and collaboration between Freud and Jung finally ended in 1913.

Jung went through a period of intense introspection and disorientation after his split from Freud. Jung was incredibly productive during this turbulent time, which saw the development of his unique psychological system: analytical psychology. And while he departed from Freudian orthodoxy, Jung continued to acknowledge his debt to Freud’s theories.

How is Carl Jung’s psyche model different from Freud’s?

Freud’s psyche model focused on repressed desires and personal experiences, while Jung’s model emphasized the collective unconscious and its archetypes. Freud’s psyche model had a tripartite structure: the instinctive id, the reality-bound ego, and the moralistic superego. Freud believed that sexuality (libido) is the primary driving force of the psyche, while the unconscious primarily stores repressed desires and childhood conflicts.

In contrast, Jung proposed a more complex model that broke the unconscious into the personal collective layers. The universal unconscious, according to Jung, is a universal psyche layer that contains inherited archetypes, which ultimately shape our behaviors and experiences. Moreover, Jung believed that the psyche wasn’t driven solely by sexuality but rather by a deep urge toward wholeness and individuation.

What is the difference between self and psyche?

The Self embodies wholeness and is the organizing principle of the psyche, while the psyche represents all conscious and unconscious mental processes. However, Jung stressed that we should not confuse the Self with the ego. The ego is our conscious sense of identity that’s a component of the larger psyche, alongside the personal and collective unconscious. While the ego helps us navigate the world, it becomes overly identified with social roles, expectations, and our conscious personality (the persona). Meanwhile, the Self is an archetype that transcends the limited perspective of the ego. It embodies the integration of all aspects of our being – our strengths, weaknesses, and our shadow elements. Achieving a greater sense of alignment with the Self brings a sense of unity and purpose.

What is self-realization according to Carl Jung?

Self-realization (otherwise known as individuation) was the ultimate goal of psychological development according to Carl Jung. It’s a lifelong process of becoming the fullest, most authentic version of ourselves. Unlike the Freudian focus on resolving past conflicts or achieving a “normal” personality, Jung’s individuation involves consciously integrating all aspects of the psyche, including elements relegated to the unconscious.

What is the significance of the Shadow archetype?

The significance of the Shadow lies in four key concepts: it impedes conscious intentions; it’s essential for individuation; it holds untapped potential; and it’s particularly dangerous in a collective. Firstly, a Shadow that’s left unacknowledged can sabotage our conscious intentions. This subversive behavior manifests through projections, compulsions, unexplained emotional outbursts, and self-defeating patterns. Secondly, Jung believed that confronting and integrating the Shadow is essential for wholeness and individuation. Conversely, ignoring or fighting our shadow keeps us fragmented and limits our personal growth. Thirdly, Jung recognized that the Shadow can be a source of creativity and vitality. Integrating the Shadow into the Self gives us access to these hidden resources. Finally, Jung warned of the danger of collective shadows. When societies or groups disown their negative aspects, there’s a risk of them being projected onto scapegoats. This process usually leads to prejudice and violence.

What are the twelve brand archetypes based on Carl Jung?

Marketers have identified the twelve brand archetypes below based on Carl Jung’s theory.

- The Creator: Driven by innovation, imagination, and self-expression. Values originality and desires to leave a lasting mark. Apple is an example of The Creator archetype because of its emphasis on sleek design and revolutionary technology.

- The Caregiver: Motivated by compassion, nurturing, and protection. Provides support, care, and a sense of belonging. Johnson & Johnson exemplifies The Caregiver archetype, as its products are rooted in safety, gentleness, and self-care.

- The Everyman: Represents down-to-earth qualities, connection, and belonging. Promotes authenticity, relatability, and inclusivity. IKEA is an example of The Everyman brand as it offers egalitarian, functional, and affordable furniture solutions.

- The Hero: Embodies courage, determination, and overcoming challenges. Inspires others to act and achieve their goals. Nike showcases the brand’s innate Hero archetype with their famous “Just Do It” slogan.

- The Outlaw: Challenges the status quo, disrupts norms, and seeks liberation. Values authenticity and breaking free from restrictions. A prime example of The Outlaw archetype is Harley Davidson, which is associated with a rebellious spirit and a sense of freedom.

- The Magician: Focused on transformation, making dreams a reality, and expanding knowledge. Seeks deeper understanding and envisions possibilities. Disney embodies The Magician archetype by creating immersive experiences that transport audiences to fantastical worlds.

- The Innocent: Embodies optimism, purity, and the desire for a simpler world. Projects happiness, goodness, and a sense of renewal. Dove’s celebration of natural beauty and one’s inherent worth exemplifies the brand’s Innocent archetype.

- The Explorer: Embraces freedom, adventure, and discovering new experiences. Values authenticity, autonomy, and pushing boundaries. North Face is an example of The Explorer archetype, with its gear and messaging encouraging adventure and outdoor exploration.

- The Ruler: Represents leadership, control, and responsibility. Seeks to create order, structure, and prosperity. Rolex exemplifies The Ruler archetype because of its status as the world’s most luxurious watchmaker.

- The Lover: Driven by passion, intimacy, and the pursuit of beauty. Values connection, pleasure, and harmony. Chanel is an example of The Lover archetype with its elegant designs and sensual, sophisticated fragrances.

- The Jester: Embodies playfulness, humor, and spontaneity. Brings joy and lightheartedness, yet challenges the status quo. An example of The Jester archetype is M&Ms, with their playful mascots and emphasis on the fun side of candy.

- The Sage: Represents wisdom, knowledge, and the pursuit of truth. Offers guidance and understanding, and shares insights. National Geographic embodies The Sage archetype with its focus on education, exploration, and sharing knowledge of the natural world.

The archetypes above help brands differentiate themselves in the market, fostering meaningful connections with consumers based on shared human desires and motivations.

How is Carl Jung’s personality types theory related to the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)?

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is inspired by Carl Jung’s theory of psychological types. However, the MBTI expands on Jung’s concepts to create a more practical framework for understanding personality differences.

Both the MBTI and Jung’s typology share the concepts of Introversion-Extraversion, Thinking-Feeling, and Sensation-Intuition. However, the MBTI adds a fourth dimension, Judging-Perceiving, to show whether a person prefers a structured approach (Judging) or an open-ended one (Perceiving). The addition of Judging and Perceiving functions creates a total of 16 personality types within the MBTI system.

Jung’s work was primarily theoretical: he devised his typology to better understand the psyche’s structure. Meanwhile, the MBTI was designed as a practical tool for self-assessment and is now common in career counseling, team building, and pop psychology. That said, the MBTI faces criticism for oversimplifying the concept of personality and lacking reliability.

How did Carl Jung view mysticism?

Carl Jung was fascinated with mysticism and viewed it as a gateway to the deepest unconscious parts of the human psyche. The psychologist’s interest in mysticism is evident in his extensive studies of alchemy, mythology, Eastern religions, and Gnosticism, and the parallels he drew between mystical events and the human psyche. Jung additionally believed that mystical experiences arose from the collective unconscious, the layer of the psyche containing universal archetypes. These archetypes manifest in powerful visions, symbols, and transformative states often described in mystical traditions. Jung theorized that these mystical experiences played a role in individuation. By engaging with the symbols stemming from the unconscious, Jung suggested that one could gain insights into themselves and their place in the cosmos.

How did Carl Jung interpret religion?

Carl Jung interpreted religion as a manifestation of the human psyche in which religious narratives try to reconcile the conscious ego with the depth of the unconscious. He studied various religious and cultural traditions, and his studies revealed patterns and symbols common to cultures with little or no contact with each other. Jung recognized these symbols’ power to express the archetypes residing in humanity’s collective unconscious.

Furthermore, Jung recognized both the positive and negative aspects of organized religion. On one hand, Jung believed that religion offers a sense of belonging and provides moral guidance. On the other hand, he saw it as a possible cause of rigidity, the repression of instincts, and the projection of the Shadow onto others. Despite this balanced viewpoint, Jung himself had little interest in theological dogma or debates about the existence of God.

What was Carl Jung’s view of Christianity?

Carl Jung viewed Christianity as a powerful force in shaping Western civilization and recognized the psychological significance of its core symbols and narratives. Jung explored themes like the Trinity, which he believed symbolized aspects of the psyche, the figure of Christ—which he saw as an embodiment of the Self—and the crucifixion as a symbolic expression of inner transformation. However, Jung disliked the rigidity of Christian dogma. He believed that strict adherence to doctrine stifles individual spiritual growth and hinders the integration of unconscious elements, and the Shadow in particular.

Was Carl Jung Buddhist?

No, Carl Jung was not Buddhist. He did not adhere to the doctrines and practices of Buddhism. However, he was deeply influenced by Buddhist philosophy and incorporated many of its insights into his understanding of the psyche. Jung also believed that Eastern philosophies offered valuable perspectives for counterbalancing the materialistic and overly rational nature of Western psychology. He was specifically drawn to the three Buddhist concepts below.

- Emptiness: Jung saw parallels between the Buddhist notion of emptiness (Sunyata) and his understanding of the collective unconscious as a field of potential beyond the ego’s constraints.

- Non-Attachment: Jung believed in the importance of non-attachment to rigid beliefs. This approach mirrors the Buddhist principle of releasing attachments on the path to reducing suffering.

- Meditation: Jung valued meditation practices as a tool for accessing the unconscious and fostering a greater awareness of inner selves.

Jung respected Buddhist ideas and allowed them to influence his work. However, his psychological theory remains distinctly Western and rooted in his own culture and clinical experience.